Squats That Improve Daily Movement: Functional Strength for Everyday Life

If you’ve ever stood up from a chair, bent down to tie your shoes, climbed a set of stairs, or picked something heavy up off the floor, you’ve performed a squat. It’s one of the most fundamental movement patterns in the human body — one we use without thinking dozens, even hundreds, of times a day.

In the gym, squats are often celebrated for building strong quads and glutes, or for chasing heavier and heavier personal records on the barbell. And while strength is absolutely important, the real magic of squats lies in how they translate to the way you move through life. Functional squat variations don’t just make you stronger — they improve mobility, balance, joint health, and coordination in ways that carry over directly to everyday tasks.

Research has shown that training multi-joint, full-body patterns like squats helps preserve muscle mass, improve bone density, and enhance neuromuscular coordination well into older age. This means fewer stumbles, easier movement in and out of cars, more stability when carrying awkward objects, and less strain on your knees and hips when you crouch or pivot. In other words — strong, functional squats are an investment in your long-term independence.

The key is knowing which squat variations will give you the most “real-life” benefit. The back squat might be king for raw strength, but it’s not the only option. By training a variety of squat styles, you can address different movement angles, fix muscle imbalances, and build a foundation of strength that works for your life, not just the gym floor.

Why Functional Squats Matter

Squats are what exercise scientists call a compound movement, meaning they recruit multiple major muscle groups and joints at the same time. This makes them incredibly time-efficient and highly transferable to real-life movement.

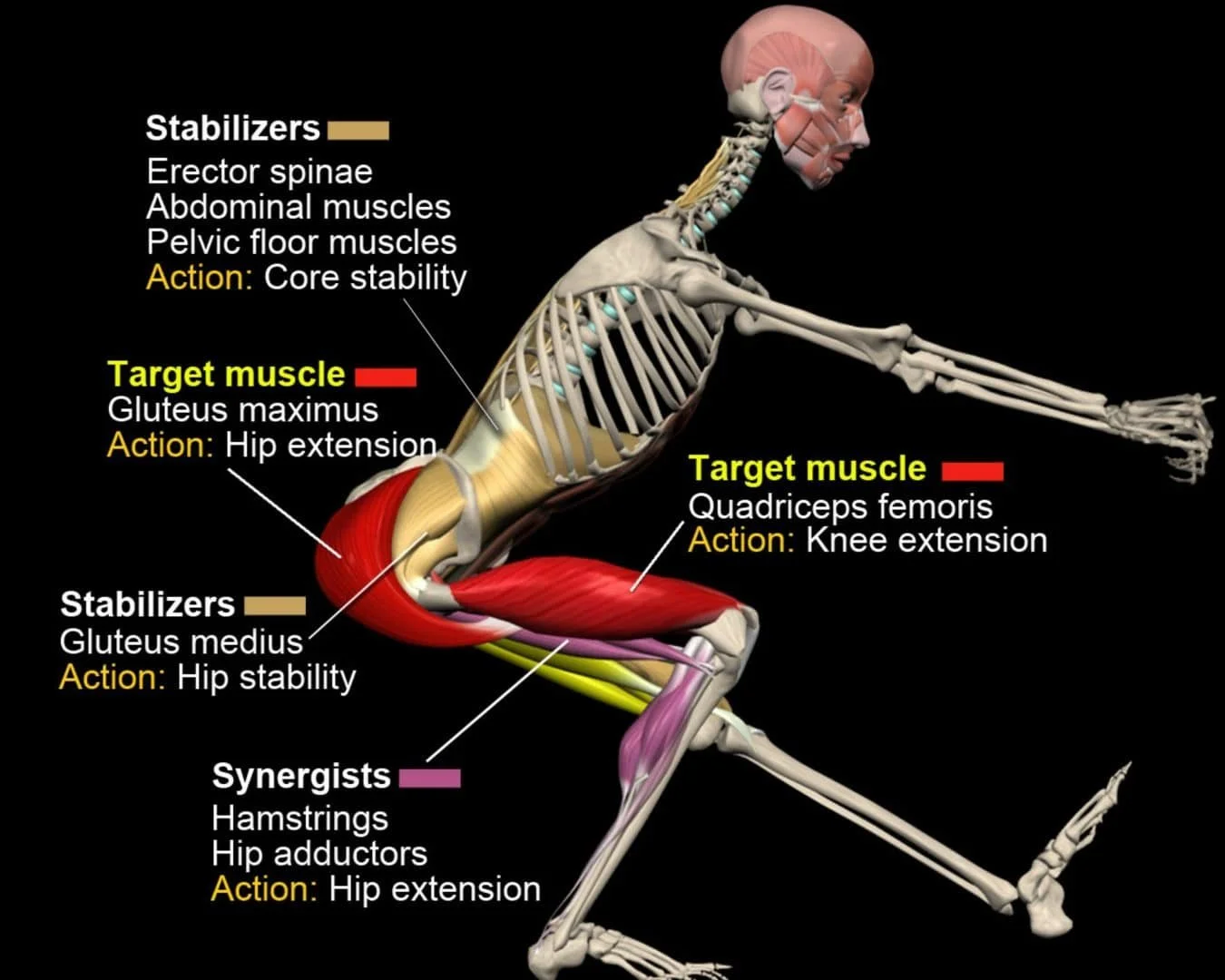

Here’s the breakdown of key muscles involved in most squat variations:

Quadriceps – Extend the knee to help you rise from the bottom of the squat.

Gluteus Maximus & Medius – Extend and stabilize the hips, powering you upward and keeping your pelvis aligned.

Hamstrings – Assist in hip extension and help control the descent into a squat.

Core Muscles (rectus abdominis, obliques, transverse abdominis) – Stabilize the spine and protect against injury.

Calves (gastrocnemius & soleus) – Support ankle stability and assist with balance.

Erector Spinae – Maintain an upright torso and resist spinal rounding.

The coordinated activation of all these muscles makes squats more than just a leg exercise — they’re a full-body stability and strength builder. This is why they play such a critical role in functional fitness and in maintaining independence as we age.

Goblet Squat

Holding a dumbbell or kettlebell in front of the chest balances posture and encourages an upright torso—much like when you pick up a child or carry groceries.

Muscles worked: Primarily quadriceps and glutes, which engage most during the lowering and rising phases. The core stabilizes the spine throughout, while the biceps and shoulders assist by supporting the front-loaded weight.

Movement plane: Sagittal (forward/backward).

Why it matters:

Enhances ankle and hip mobility—helpful for squatting down or picking items up off a low surface.

Strengthens the anterior chain without overloading the spine.

Trains bracing and intra-abdominal pressure, protecting the lower back during lifting.

Best for: Great for beginners learning squat mechanics, athletes needing stronger drive out of a squat position, or workers who frequently lift items off the ground. Its upright posture makes it a safer entry point than a back squat.

Functional tie-in: Mimics real-life actions like sitting down, standing up, or lifting groceries from the floor.

Split Squat / Bulgarian Split Squat

A unilateral movement that challenges one leg at a time, improving balance, coordination, and power.

Muscles worked: Quadriceps and glutes on the front leg do the bulk of the work, especially during the push upward. Hamstrings assist in hip extension, while hip stabilizers and core muscles keep the pelvis aligned and torso steady.

Movement plane: Primarily sagittal, with stabilization in the frontal plane to prevent wobbling.

Why it matters:

Corrects left-to-right strength imbalances, reducing injury risk.

Builds single-leg strength and stability, important for stair climbing, running, or hiking.

Engages hip abductors/adductors for pelvic stability.

Best for: Runners, field athletes, and anyone whose sport or work requires single-leg strength and stability. Also helpful for older adults looking to prevent falls by improving balance.

Functional tie-in: Trains the strength and control needed for walking, climbing stairs, or rising from a lunge/kneel — positions common in both athletics and daily tasks.

Lateral Squat

A side-to-side squat variation that strengthens the legs while building mobility in the hips and adductors. Unlike a traditional squat, you shift your weight onto one bent leg while keeping the other leg straight, then return to center.

Muscles worked: The bent leg’s quadriceps and glutes work hardest at the bottom of the squat to push you back upright. The straight leg’s adductors (inner thigh) are stretched under load and stabilize the pelvis. Hamstrings and calves help with balance and control, while the core prevents the torso from tipping forward.

Movement plane: Frontal (side-to-side), often neglected in traditional training.

Why it matters:

Builds lateral strength and mobility, key for side-to-side athletic movements.

Strengthens inner thigh muscles, supporting hip and knee health.

Improves hip mobility and stability for smoother sidestepping, pivoting, or crouching.

Best for: Athletes in sports with lateral demands (soccer, hockey, basketball), as well as workers who climb, crouch, or shift side-to-side. Also excellent for hikers navigating uneven terrain.

Functional tie-in: Trains the ability to shift weight efficiently — whether it’s sidestepping around an obstacle, crouching to grab something from the ground, or moving laterally in sport or play.

Progression to Cossack Squat: Once you’ve built a solid base with lateral squats, you can progress to the Cossack Squat, which takes the movement deeper. In a Cossack, you sink into a full-depth lateral squat while the straight leg stays extended with the toes up. This increases the demand on hip and ankle mobility, challenges balance further, and loads the adductors and glutes through a larger range of motion. It’s particularly valuable for athletes who need agility and mobility in extreme positions, like martial artists, wrestlers, or hockey players who rely on wide stances.

Turning These Into a Functional Routine

To train squats for real-world benefits:

Emphasize form over load. Quality movement patterns ensure all the right muscles are firing in the right sequence.

Use a variety of planes of motion. This ensures your muscles are prepared for forward, backward, and lateral movement in daily life.

Include tempo work to build control — slow descents load the quads, glutes, and core under time, improving strength and stability.

3-Day Functional Squat Program

Designed for all major muscle groups & planes of motion with squat progression over 4 weeks.

Training Notes:

Perform workouts on non-consecutive days (e.g., Mon/Wed/Fri).

Rest 60–90 seconds between strength exercises, 30–45 seconds between accessory or mobility work.

Progression: Increase weight by 2–5% weekly if form is solid, or add 1–2 extra reps per set.

Plan includes sagittal (forward/back), frontal (side-to-side), and transverse (rotational) plane movements.

Day 1 – Lower Body Strength + Anterior Chain Focus

Warm-Up (5–7 min)

Bodyweight Squat to Reach x 8

Walking Lunge with Rotation x 5/leg (transverse)

Cat-Cow x 5

Main Strength

Goblet Squat – 3 × 10 (Week 1–2: standard, Week 3–4: add 3-sec eccentric)

Bulgarian Split Squat – 3 × 8/side (hold dumbbells if able)

Accessory/Balance

3. Step-Up to Knee Drive – 3 × 10/leg (frontal + sagittal) 4. Push-Ups (floor or incline) – 3 × 10–12

Arms/Core

5. Biceps Curl to Press – 3 × 10

6. Pallof Press – 3 × 10/side (anti-rotation, transverse plane)

Day 2 – Full Body Functional Strength + Lateral Emphasis

Warm-Up (5–7 min)

Lateral Band Walk x 10 steps each way

Lateral Squat (bodyweight) x 6/side

Glute Bridge x 10

Main Strength

Lateral Squat – 3 × 8/side (Week 1–2: bodyweight, Week 3–4: add light dumbbell)

Single-Arm DB Row – 3 × 10/side

Accessory/Balance

3. Lateral Step-Up – 3 × 8/leg (frontal plane) 4. Dumbbell Chest Press – 3 × 10 (bench or floor)

Arms/Core

5. Overhead Triceps Extension – 3 × 10

6. Side Plank with Hip Lift – 3 × 20 sec/side

Day 3 – Posterior Chain + Rotational Strength

Warm-Up (5–7 min)

Hip Airplane x 5/side

Squat to Calf Raise x 8

Inchworm Walkout to Plank x 5

Main Strength

Tempo Bodyweight Squat – 2 min slow & controlled (Week 1–2: bodyweight, Week 3–4: add goblet hold)

Romanian Deadlift – 3 × 10

Accessory/Balance

3. Lunge with Rotation (med ball or dumbbell) – 3 × 8/side (transverse plane) 4. Dumbbell Chest Fly – 3 × 12

Arms/Core

5. Hammer Curls – 3 × 10

6. Dead Bug with Stability Ball – 3 × 10

The squat is far more than a “leg day” staple — it’s a movement that shapes the way we navigate the world around us. Every time you bend to pick something up, lower yourself into a chair, climb a step, or shift to the side, you’re relying on the same muscles, joints, and balance you train in the gym. By focusing on functional squat variations like the goblet squat, split squat, and Cossack squat, you’re not just getting stronger for the sake of lifting more weight — you’re building a body that moves with ease, resists injury, and supports you in the activities that matter most.

Think of it this way: a heavy back squat might set a personal record on paper, but a well-trained functional squat pattern sets you up for personal records in everyday life. That could mean carrying groceries up a flight of stairs without stopping, squatting down to garden without feeling stiff, or having the balance and mobility to chase your kids or grandkids across the yard.

And the benefits go well beyond strength. Functional squat training supports joint health by moving through full ranges of motion, improves coordination by challenging balance and stability, and even encourages healthier posture through core engagement and spinal alignment. Over time, this means more than just looking fit — it means staying capable, confident, and mobile well into the decades ahead.

If you take one thing from this article, let it be this: your squat is an investment. Every rep you put in today pays off in the way you move tomorrow. Train your squat not just for the numbers on the bar, but for the life you want to lead outside the gym.

Hope that helps,

Happy Exercising!

📚 References

Contreras, B., Vigotsky, A. D., Schoenfeld, B. J., Beardsley, C., & Cronin, J. (2015). A comparison of gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and vastus lateralis EMG amplitude in the parallel, full, and front squat variations. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 31(6), 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1123/jab.2014-0301

McCurdy, K., Langford, G., Doscher, M., Wiley, L., & Mallard, K. (2005). The effects of unilateral vs. bilateral lower-body resistance training on measures of strength and power. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1519/00124278-200502000-00002

Speirs, D. E., Bennett, M. A., Finn, C. V., Turner, A. P., & Kilduff, L. P. (2016). Unilateral vs. bilateral squat training for strength, sprints, and agility in academy rugby players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(2), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001096

Choi, J., & Kim, D. (2015). Effects of lateral squat exercises on hip adductor and abductor strength. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(9), 2891–2893. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.2891

DeForest, B. A., Cantrell, G. S., & Schilling, B. K. (2014). Muscle activity in single- vs. double-leg squats. International Journal of Exercise Science, 7(4), 302–310. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijes/vol7/iss4/6

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3497–3506. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac2d7

Boyle, M. (2016). New Functional Training for Sports (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics.