Training With a Degenerative Meniscus Tear

Knee pain isn’t new—it’s as old as sport itself. Historical medical records going back to early orthopaedic writings in the 19th and early 20th century describe “internal derangements of the knee,” often referencing meniscal damage. Back then, any knee injury was likely treated with long rest, crude bracing, or—in more severe cases—removal of the entire meniscus. The belief at the time was that the cartilage was nonessential. Unfortunately, removing it entirely often led to accelerated arthritis, and by the mid-20th century, surgeons and researchers began to understand the protective role the meniscus plays in shock absorption, load distribution, and joint stability.

Degenerative meniscus tears, in particular, aren’t caused by one dramatic injury. Instead, they develop gradually as the cartilage weakens with age and years of repetitive stress. Think of it like the slow fraying of your favorite jeans—little by little until there’s a tear. They’re extremely common in adults over 40, especially those with a history of sports, heavy lifting, or repetitive occupational kneeling and squatting. Modern imaging studies even show that a large percentage of middle-aged and older adults have degenerative tears without any symptoms at all—a finding that has completely shifted how we think about diagnosis and treatment.

Historically, surgery was the go-to treatment—even for these gradual wear-and-tear injuries. For decades, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (removing the torn portion) was one of the most common orthopedic procedures worldwide. But in the last 10–15 years, high-quality research has shown that for most degenerative tears, structured rehabilitation and progressive strengthening can be just as effective as surgery—sometimes more so, since you keep the meniscus tissue intact. This has led to a major shift in treatment recommendations from orthopedic and sports medicine organizations globally.

As a trainer, I’m not here to replace your medical team. I’m here to help you understand the “why” behind training with a degenerative meniscus tear, how to move in a way that supports healing, and how to build strength so your knee feels stable and capable. In this guide, we’ll look at what’s actually going on inside the joint, why exercise is often the best first-line approach, and how to train smart—covering all planes of motion—without setting yourself back.

What We’re Actually Dealing With

A degenerative meniscus tear is slow, age-related fraying of the knee’s shock-absorbing cartilage—more like worn jeans than a fresh rip. By midlife, a surprising number of people have meniscal “damage” on MRI without any knee pain at all.

Why is that?

Pain isn’t caused by the meniscus itself being “torn” — the meniscus has very few nerve endings, especially in its inner portion. That means the tissue can fray or split without sending a pain signal. Pain usually comes when there’s inflammation, swelling, or mechanical irritation inside the joint — for example, if a flap of tissue catches in the joint, or if the surrounding synovium (joint lining) becomes irritated.

In degenerative tears, the changes often happen slowly enough that your body adapts. Muscles and movement patterns shift to protect the joint, and the nervous system doesn’t register it as an immediate “threat.” This is why many people have visible “damage” on MRI but feel fine — and why imaging alone is not a reliable indicator of whether you need treatment or surgery. What matters most is how your knee behaves in daily life, not just what the scan shows

Why Training (Often) Beats the Scalpel

High-quality trials show exercise-based physiotherapy performs just as well as arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) for pain, function, and quality of life — not only in the short term, but even at 5-year follow-up. This is why many orthopedic and sports medicine guidelines now recommend rehab first for most degenerative meniscus tears.

The “why” behind that, with science to back it up:

1. Muscle as medicine.

Strong quadriceps and hamstrings act like dynamic shock absorbers, helping share the load with the meniscus and reduce stress on the joint. In the ESCAPE Randomized Clinical Trial (van de Graaf et al., 2022), participants who completed a 16-session progressive exercise program had outcomes equal to those who underwent APM — both at 2 years and at 5 years. The difference? The exercise group kept their meniscal tissue, which may help reduce future arthritis risk. Other studies have confirmed that greater quadriceps strength is linked to less pain and better function in people with degenerative meniscus tears (Culvenor et al., 2017).

2. Hip control = knee control.

The hips play a bigger role in knee health than most people realize. Strong abductors and external rotators help prevent dynamic valgus — that inward collapse of the knee — which increases stress on the inside of the joint. Randomized controlled trials have shown that adding hip strengthening to a knee rehab program produces greater improvements in pain and function compared to quadriceps-only training (Bennell et al., 2010).

3. Smart loading helps cartilage and meniscus health.

Cartilage and meniscal tissue rely on a process called mechanotransduction — controlled, cyclical loading stimulates nutrient exchange via synovial fluid, promotes proteoglycan synthesis, and keeps the tissue resilient. In simple terms, movement literally feeds your joint. Research has shown that prolonged rest or immobilization accelerates cartilage degeneration, while appropriately dosed loading maintains or improves tissue quality (Andriacchi & Mündermann, 2006; Griffin & Guilak, 2005). Overload can irritate the joint, but the right balance of stress and recovery keeps it healthier for longer.Training Principles I Use With Clients

Calm the joint, then load it. No spikes in pain during or after sessions, no next-day balloon knee.

All planes, controlled ranges. Sagittal (forward/back), frontal (side-to-side), transverse (rotation)—but earn the range first.

Criteria > calendar. Progress when you meet milestones (no swelling, good control), not just because “it’s week 4.”

Phase-Based Plan (With the “Why” Baked In)

Phase 1 — Settle & Rebuild (Weeks 1–3)

Goal: restore motion, quiet symptoms, turn muscles “back on.”

Bike, easy 10–15 min (promotes synovial fluid movement—nourishes cartilage without shear)

Heel slides 2–3×12 (gentle flexion nutrition for cartilage)

Quad sets 3×10 (recruit VMO/quad without joint compression)

Straight-leg raise 3×10 (anterior chain without knee bend)

Progress check: full extension, ≥120° pain-tolerable flexion, quiet knee after daily life.

Phase 2 — Strength & Control (Weeks 4–8)

Goal: build shock-absorbers (quads/hams/glutes), groove knee alignment.

Wall sits @ ~45–60° 3×30–45s (isometrics reduce pain, load quads safely)

Step-ups (low box) 3×8/leg (closed-chain quad load; watch knee track)

Hamstring bridge (feet elevated) 3×10 (posterior chain balances tibial forces)

Lateral band walks 3×12/side (hip abductors fight valgus)

Anti-rotation press (Pallof) 3×10/side (core resists transverse wobble)

Progress check: no swelling, RPE ≤6/10, stable knee in single-leg stance 30–45s.

Phase 3 — Return to “Real” Training (Week 8+)

Goal: load tolerance + multi-plane power under control.

Sled push/pull 4×20–25 m (horizontal force without deep knee angles)

Goblet squats to a box 4×6–8 (progress depth slowly; tempo 3-1-1)

Lateral step-downs 3×8/side (eccentric frontal-plane control)

Cable or landmine anti-rotation walkouts 3×8/side (transverse plane)

Optional low-amplitude plyo (line hops or step jumps) 3×10—only if zero next-day reactivity

A Complete Workout Day (All Planes, 45–55 min)

Warm-up (8–10 min)

Bike 5 min → Hip airplanes (supported) 2×5/side → Heel elevated calf raises 2×12

Activation (6 min)

Mini-band lateral walk 2×12/side → Terminal knee extension (band) 2×12

Strength circuits (25–30 min)

A1. Goblet squat to box (sagittal) 4×6–8 @ RPE 7

A2. Half-kneeling Pallof press (transverse anti-rotation) 4×8/side

B1. Lateral step-down or skater step-down (frontal) 3×8/side @ slow tempo

B2. Hamstring bridge (feet on box) 3×10

C1. Sled push (horizontal) 3×20–25 m

C2. Split-stance cable row (anti-rotation demand) 3×10/side

Finisher / capacity (5 min)

Farmer carry (double) 3×30–40 m

Movements I Usually Modify Early On (And Why)

Deep knee angles under load: compressive and shear forces spike in flexion; save for later phases.

Twist + load: transverse shear can flare symptoms—add only after frontal/sagittal control is solid.

High-impact plyos: progress from small hops → step jumps → low box; monitor next-day knee.

When Surgery Might Be on the Table (and why exercise sometimes isn’t enough)

Most mid-life, wear-and-tear meniscus tears do just as well with a solid rehab block as they do with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM), even out to 2–5 years—hence the modern “rehab first” recommendation. But there are clear situations where surgery is reasonable or preferred. BMJNew England Journal of Medicine+1PubMed

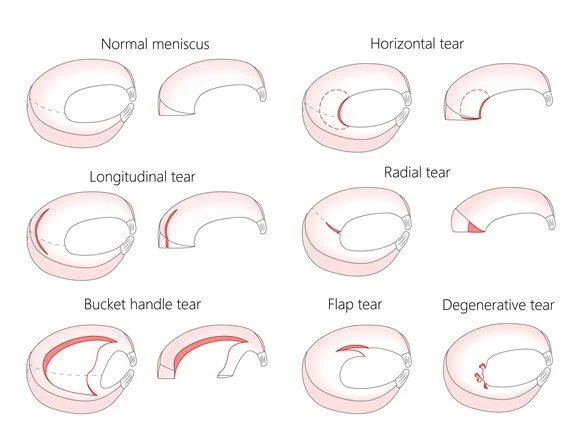

1) True mechanical symptoms (not just “clicky” knees)

If a displaced fragment physically blocks motion—classically a bucket-handle tear—you’ll see loss of extension, repeated catching/locking, and swelling that won’t settle with good rehab. In these cases, the fragment keeps irritating the joint lining (synovium) and cartilage; removing or repairing it restores smooth joint mechanics. That’s the kind of “mechanical problem” exercise can’t fix. Current guidelines that generally discourage arthroscopy for degenerative disease still acknowledge exceptions for persistent mechanical locking. PubMedBritish Journal of Sports Medicine

2) Posterior root tears with extrusion (biomechanics matter)

The meniscus works by “hoop tension”—it spreads load around the rim like a belt. A posterior root tear severs that belt, the meniscus extrudes outward, and contact pressures in the medial compartment jump dramatically—laboratory work shows pressures similar to a total meniscectomy. In this specific pattern, repair (not trimming) can restore near-normal contact mechanics and protect cartilage; leaving it as-is can accelerate arthritis. This is one of the clearest biomechanical indications for surgery. PubMedSensorProdPMCResearchGate

3) Acute traumatic tears in younger or athletic patients

Vertical-longitudinal or bucket-handle tears in the vascular zone (the “red-red” or “red-white” rim) following a clear injury often do best with meniscal repair to preserve tissue long term—especially when combined with ACL reconstruction. Here the goal is joint preservation over decades; exercise can’t re-approximate torn vascular tissue that’s mechanically unstable. (Contrast this with frayed, horizontal degenerative splits in mid-life, which rarely need a scope.) PubMed

4) High-quality rehab… but no progress

If you’ve completed 8–12+ weeks of well-progressed, criteria-based rehab (strength, control, load tolerance) and still have function-limiting pain, swelling, or inability to achieve daily tasks, a surgical opinion is reasonable. Importantly, the best RCTs show many patients who started with PT and later chose surgery still did just as well as those who went straight to surgery—so trying rehab first is rarely a “missed window.” PubMed+1

5) What surgery does not solve well

APM for degenerative tears with osteoarthritis tends to underperform. Multiple RCTs—including a sham-surgery trial—found little to no clinically meaningful advantage of APM over structured exercise (or even placebo surgery) for pain and function. That’s why the BMJ guideline makes a strong recommendation against routine arthroscopy in most degenerative knee disease. If the whole joint is irritable (cartilage/bone/synovium), trimming a frayed edge won’t change the biology driving symptoms. New England Journal of MedicinePubMed+1BMJ

Quick decision snapshot (how I explain it to clients)

Rehab first if: mid-life degenerative tear, no true locking, swelling manageable, goals are strength/function. Expect PT to match surgical outcomes at 1–5 years while keeping your meniscus. BMJNew England Journal of Medicine

Ask ortho sooner if: you can’t fully straighten, the knee repeatedly locks, or imaging shows a root tear with extrusion (and your symptoms match). Those are mechanical problems where a repair/arthroscopy may restore joint mechanics. PubMed+1

Bottom line: exercise changes the system—muscle, control, load sharing, synovial nutrition. Surgery addresses a mechanical block or re-establishes critical meniscal function (like hoop tension) when it’s truly lost. Picking the right tool for the right problem is what gets you back to training fastest—and keeps you there.

Move what you can, where you can, as cleanly as you can—then progress the dose. If your knee stays quiet 24–48 hours after sessions, you’re winning. If it talks back, we adjust the how much before we ditch the what.

Hope that helps,

Happy Exercising!

References

van de Graaf, V. A., Noorduyn, J. C. A., Willigenburg, N. W., Butter, I. K., de Gast, A., Mol, B. W., ... & Reijman, M. (2022). Effect of Early Surgery vs Physical Therapy on Knee Function Among Patients With Nonobstructive Meniscal Tears: Five-Year Follow-up of the ESCAPE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open, 5(7), e2220394. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.20394

Culvenor, A. G., Ruhdorfer, A., Juhl, C., Eckstein, F., Øiestad, B. E., & Crossley, K. M. (2017). Quadriceps strength is a significant determinant of knee pain and function in patients with meniscal tears. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(3), 219–225.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096348

Bennell, K. L., Hunt, M. A., Wrigley, T. V., Lim, B. W., Hinman, R. S. (2010). Effects of hip muscle strengthening on pain and function in people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care & Research, 62(8), 1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20268

Andriacchi, T. P., & Mündermann, A. (2006). The role of ambulatory mechanics in the initiation and progression of knee osteoarthritis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 18(5), 514–518.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bor.0000240365.16842.4e

Griffin, T. M., & Guilak, F. (2005). The role of mechanical loading in the onset and progression of osteoarthritis. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 33(4), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003677-200510000-00008

Siemieniuk, R. A. C., Harris, I. A., Agoritsas, T., Poolman, R. W., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Van de Velde, S., Buchbinder, R., Englund, M., Bain, C., & Johnston, R. V. (2017). Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ, 357, j1982. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1982

LaPrade, R. F., et al. (2014). Meniscal root tears: a classification system based on tear morphology. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(3), 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546513516949

Papalia, R., Vasta, S., Franceschi, F., D’Adamio, S., Maffulli, N., & Denaro, V. (2011). Meniscal root tears: from basic science to ultimate surgery. British Medical Bulletin, 99, 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldr003